Gut Health and Pain – Part 3: Your Gut and Stress

Over the past decade there has been a lot of discussion about the importance of our gut. Our gut has been shown to be one of the keys to our overall health and wellbeing.

- It has been called our “second brain” due to the intricate nervous system (the enteric nervous system) it holds within in and how it communicates with our brain (the gut-brain axis).

- It has been shown to play a vital role in the production of serotonin, which has been one of the keys to understanding the role it plays in mood and sleep.

- It has been shown to play a vital role in our stress (hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis) and relaxation (through the vagus nerve) response.

- It is home to 100 trillion microorganisms and their genetic material, known as microbiome, and scientists are only just unlocking the potential of this live bacteria.

- Some of the most interesting areas being explored by scientists include the role our gut plays in immunity, inflammation and pain.

The following series “Gut Health and Pain” will take a look at the intricate world of our gut and unravel the mystery of why there is thousands journal articles being written each year about the health of our gut and the problems an unhealthy gut can cause. Welcome to Part 3 – Your Gut and Stress.

Part 3 – Your Gut and Stress

In our last article we discussed the link between our gut and our brain, the role it plays in our mood, how nutrition plays a role in pain and sleep and some of the emerging research in this fascinating field. In this article we will discuss:

- A recap on the basics of nutrition and weight

- What is the link between nutrition, our stress response and pain?

- Prolonged stress: the toll on your weight, metabolism and pain

- The relationship between our gut and stress response?

- The relationship between our gut and relaxation response?

A recap on the basics of nutrition and weight

As we discussed in our first article, good nutrition is essential for our health and wellbeing. What we eat and drink becomes the foundation of our overall health and wellbeing, making up the structure, function and integrity of every single cell in our bodies. Nutrition also allows us to transfer energy from the food we eat and what we drink, and convert this to:

- Keep us alive (digestion, our heart beating, our lungs breathing etc)

- Assist us with any mental activities (we burn about 320 calories thinking every day, this increases by 5% depending on the complexity of the thought)

- Assist us with any physical activity we do

85% of our daily energy comes from fat and carbohydrates and 15% from protein; energy is measured in calories or kilojoules. When our body is in balance (there are no other underlying health issues, hormone imbalances, and we are not in a period of prolonged stress):

- To maintain a healthy weight our “energy in” needs to be equal to our “energy out”

- To gain weight our “energy in” needs to exceed our “energy out”

- To lose weight our “energy out” needs to exceed our “energy in”

Interestingly, all areas of weight management (when your body is in equilibrium) fall under 3 types of restriction:

- Caloric restriction (as shown above) – how much we eat, the quantity consumed

- Time restriction – when we do and don’t eat (intermittent, time-restricted fasting etc.)

- Dietary restriction – what we eat and what we don’t (paleo, vegetarian, vegan, plant-based, carnivore etc.)

But what happens when our bodies go through periods of prolonged stress? How does this affects our gut, pain and nutrition?

What is the link between nutrition, our stress response and pain?

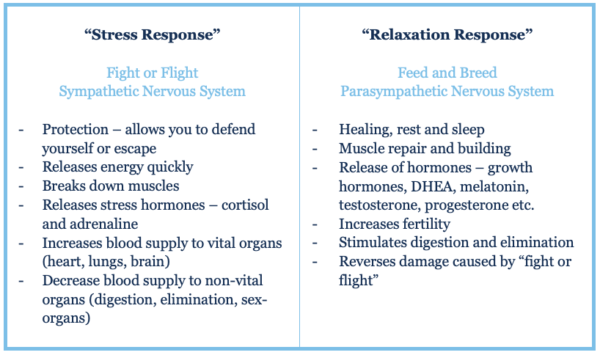

Stress and chronic pain have been referenced as the two sides to the same coin. Pain and stress are protective mechanisms associated with our “fight or flight” response (sympathetic nervous system) and are known to cause negative changes in our physical, emotional and mental health when they become chronic. Let’s quickly recap on two important systems in our body and two important hormones:

- Hormone: Cortisol – The “stress hormone” cortisol is released during periods of stress; its role is slowing body processes that are not essential to survival. The challenge is that when levels remain high for prolonged periods, they cause memory issues, poor healing, libido issues, depression, decreased physical performance and metabolic issues.

- Hormone: Adrenaline – This is another hormone released by our body during periods of stress; its role is activating a lot of the physiological changes in our body during fight or flight (increased heart rate, increased respiratory rate etc.). The challenge is when levels remain high for a prolonged period it magnifies pain messages due to changes to the body (inflammation, nerve damage, increased adrenaline receptors) and alters our metabolism.

Prolonged Stress: the toll on you, your weight and your pain

Chronic pain is considered a state of prolonged stress in your body, where our body remains in a persist state of high alert to danger, threats and perceived threats. The challenge is that this prolonged state of stress can lead to prolonged, high levels of cortisol and adrenaline. Cortisol, adrenaline and stress affect our metabolism and weight (learn more here):

- Increasing the secretion of glucose from our liver, which increases our blood sugar levels

- Decreasing the hormones responsible for removing excess glucose from your blood – insulin

- Glucose being stored as fat

- Decreasing the ability to clear excess hormones from our liver, leading to increasing circulation of unnecessary hormones like cortisol, oestrogen etc.

- Increasing our appetite and attention to food (this is due to our cave men “fight or flight” memory that prolonged stress usually meant famine or food shortage)

- Storing excess weight to weather the storms (once again due to the “fight or flight” memory).

Prolonged stress can prevent effective weight-loss by traditional means, such as calorie restriction because this only further reinforces the message that there is a food shortage, and exercise only adds further fuel to our “fight or flight” stress response – as exercise activates this sympathetic nervous system response in our bodies. Some additional side effects of prolonged stress include imbalances to our sex-hormones, such as oestrogen dominance; changes to our hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis; and changes to our thyroid and growth hormones; all of which have an impact on healthy weight, metabolism and weight-loss.

Often in situations of prolonged stress, the most effective weight management strategies come from stress-management, deep breathing exercises (our breath is the only way to tap into our sympathetic nervous system), relaxation activities (such as meditation, yoga and Tai Chi) and small, regular, healthy meals.

What is the relationship between our gut and stress response?

What is the relationship between our gut and stress response?

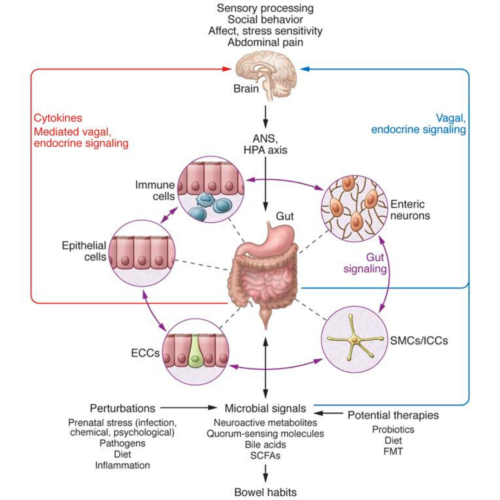

The gut plays an important role in our stress response; when exposed to stressful stimulus, the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis, and the sympathetic nervous system are activated to maintain balance in the body. Researchers have identified that “gut microbiota can play a critical role in the development and regulation of the HPA response to stressors”.

The HPA axis is central to our stress response and is responsible for the release of hormones (including adrenaline and cortisol) from our hypothalamus, pituitary and adrenal glands. The gut and gut microbiome play an important role in regulating levels of cortisol, which are released by the HPA; there are ongoing studies looking at the link between specific gut microbiome and the HPA axis and how this can be used in chronic stress states.

Another interesting area of research involves how early life trauma may effect our gut microbiome and response to stress. Emerging research is looking at how early life trauma/stress affects the diversity of microbiome. Scientists have been conducting lab-based experiments where the microbiome was removed entirely from animals; interestingly these microbiome-free animals had exaggerated responses to stress. These microbiome-free animals had marked alterations to their brain and how they dealt with stress.

This has led researchers to ask the question: could we modify our stress response by targeting our microbiome? Researches are currently looking at how different strains of microbiome may target specific conditions, like stress and pain, this is an evolving area of medicine. This is a particularly interesting area of research because there have been so many studies looking at early life trauma and the development of chronic pain later in life.

Another interesting area of research, is looking at neurotransmitters and the gut, and whether we can modulate specific neurotransmitters and/or their related pathways. Many of our neurotransmitters are made in our gut, including 90% of our serotonin, which plays an important role in the processing of pain. Researchers have been looking at whether supplementation of specific probiotics can change levels of neurotransmitters, or affect the pathways of these neurotransmitter. Although further research is needed, this could have some interesting applications for stress, pain, mood, sleep and weight.

The relationship between our gut and relaxation response?

The relationship between our gut and relaxation response?

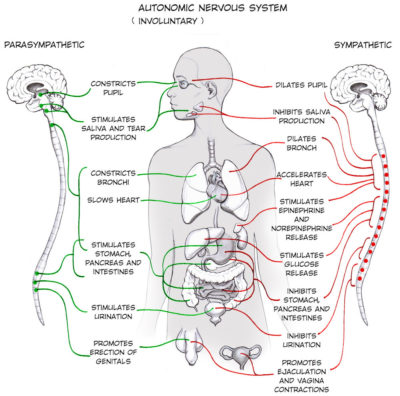

The vagus nerve plays a crucial role within the parasympathetic nervous system, which is part of your autonomic nervous system. It is our unconscious system which is responsible for our relaxation response – the “rest and digest” and “feed and bread” functions. The word “vagus” in Latin means wandering, which is exactly what this nerve does, running from our brain stem to our colon. It connects a vast majority of our major organs, particularly those which make up our gut, and allows communication between them and our brain.

The vagus nerve consists of two afferent (sensory) pathways; the somatic – the sensations we feel in our muscles and skin, and the visceral – the sensations we feel in the organs inside our body. It also consists of efferent (motor) pathways, which are involved with stimulating the muscles within our mouth and throat, stimulating our heart and stimulating the involuntary movements within our gut which allow food to move through.

The vagus nerve is thought to be largely responsible for the mind-body connection (gut-brain axis). It appears to play a crucial role in our thoughts, feelings and behaviours. It is also believed that stimulating the vagus nerve may trigger the relaxation response, reducing heart rate and blood pressure.

Our vagus nerve is part of our unconscious automatic nervous system, meaning it is involved with involuntary responses like our heart rate, digestion and breathing, to name a few. One of the only ways to trigger the relaxation response is through diaphragmatic breathing. Slow, deep breathing puts the “brake” on our stress response. Sensory nodes in our lungs, send information to our brain via the vagus nerve. The vagus nerve then sends a message to our heart to either increase (if our breathing is fast) or decrease (if our breathing is slow).

It has been suggested that harnessing the power of our parasympathetic nervous system may reduce the symptoms associated with chronic pain. Interesting, our vagus nerve may be one way to tap into this usually subconscious system. So, can we improve our vagus nerve health? Our vagus nerve is similar to a muscle – we can improve its strength through exercising it. Research suggests: diaphragmatic breathing, laughing, singing, humming, yoga, tai chi, cold-water showers and cold-water swimming; could all improve the health of our vagus nerve.

Some other interesting areas of research include:

- Looking at vagus nerve health, the brain and the experience of pain, and how improving vagus nerve health may alter the brain and pain.

- Looking at the use of neuromodulation for stimulating your vagus nerve to modulate many conditions, including some preliminary studies with pain, this is a fascinating and evolving area of medicine.

- Looking at the vagus nerve, neurotransmitters and our gut. The vagus nerve connects the gut and brain, through the gut-brain axis. It communicates information from the gut to the brain using neurotransmitters (such as serotonin and glutamate) and gut hormones, all of which play a vital role in sleep, mood, pain, stress and hunger. Researches believe that improving gut health through diet, probiotics and even potentially fecal microbial transplantation(FMT), may improve our gut-brain axis.

- How changing vagus nerve function may have an impact on inflammation within the body. Inflammation plays a role in neuroinflammation (a process which affects the health and disease of the nervous system by regulating the development, maintenance and sustenance of brain cells and their pathways) which is considered one of the drivers of chronic pain and central sensitisation.

Continue reading: Part 4 – Changing Your Gut Health here

Additional references

- Journal Article: Eubiosis and dysbiosis: the two sides of the microbiota (article here)

- Article: Our gut microbiome is always changing; it’s also remarkably stable (link here)

- Book: Gut Health and Probiotics. The science behind the hype. Jenny Tschiesche

- Book: Rushing Woman’s Syndrome. The impact of a never ending to-do list on your health. Dr Libby Weaver

- Book: Gut. The inside story of our body’s most under-rated organ. Giulia Enders

- Book: The mind-gut connection. How the hidden conversation within our bodies impacts on our mood, our choices, and our overall health. Emeran Mayer, MD

- Journal Article: The Role of Gut Microbiota in Intestinal Inflammation with Respect to Diet and Extrinsic Stressors (article here)

- Journal Article: Stress and the gut microbiota-brain axis (article here)

- Journal Article: The gut microbiome: Relationships with disease and opportunities for therapy (article here)

- Journal Article: Neurotransmitter modulation by the gut microbiota (article here)

- Journal Article: The microbiome: A key regulator of stress and neuroinflammation (article here)

- Journal Article: Role of gut microbiota in brain function and stress-related pathology (article here)

- AUSMED E-Learning: Gut Microbiota Health and Wellbeing (link here)

- Journal Article: A review of lifestyle factors that contribute to important pathways associated with major depression: Diet, sleep and exercise (article here)

- Journal Article: ‘Gut health’: a new objective in medicine? (article here)

- Journal Article: Nutritional stimulation of the autonomic nervous system (article here)

- Journal Article: Influence of Tryptophan and Serotonin on Mood and Cognition with a Possible Role of the Gut-Brain Axis (article here)

- Journal Article: Gut microbiota regulates mouse behaviours through glucocorticoid receptor pathway genes in the hippocampus (article here)

- Journal Article: Cognitive and emotional control of pain and its disruption in chronic pain (article here)

- Journal Article: Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve (article here)

- Journal Article: Microbiome, HPA axis and production of endocrine hormones in the gut (article here)

- Book: Microbial Endocrinology: The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Health and Disease. Vagal Pathways for Microbiome-Brain-Gut Axis Communication.

- Journal Article: Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain–Gut Axis in Psychiatric and Inflammatory Disorders (article here)

- Journal Article: The Vagus Nerve at the Interface of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis (article here)

- Journal Article: Gut Microbes and the Brain: Paradigm Shift in Neuroscience (article here)

- Article: Monash University: Prebiotic diet – FAQs (link here)